Rediscovering the measurement system used by pre-European Māori

A student research project supported by Callaghan Innovation’s Measurement Standards Laboratory (MSL) has looked at the measurement systems used by pre-European contact Māori. The study has found anecdotal evidence that Māori used a standard measure of length for building and developed a decimal numbering system, both of which were used in the building of whare and other structures. Click below for the full report.

Ngā Inenga Māori: A Preliminary Study on Māori Measurement [PDF, 489 KB]

If you have information or evidence that would support the findings of this paper or provide opportunities for further research on this topic, please contact the Measurement Standards Laboratory.

Summary

The idea for the study originally arose from a written account of a pre-European standard measure of length used by Māori, known as a Rauru. The Rauru had been referred to by the 19th and 20th century historian Elsdon Best, which he described as a measuring tool that could be used and reused over generations in some cases.

This identified a research question, to find out whether pre-European contact Māori had understood the concept of a repeatable and reliable measurement system and were using a primary length standard for building and perhaps trade purposes.

MSL enlisted a Victoria University of Wellington student, Te Aomania Te Koha, to look more deeply into the question. Under the supervision of Dr Farzana Masouleh, she undertook a research project over the summer and wrote a report that draws heavily on the writing and research of Best. Best has written that Māori had their own system of measurement before European colonists arrived in New Zealand in the 1830s and 1840s, using lengths between different parts of the body to make measurements when building waka and whare. This alone would not be unusual, as many other civilisations have done this, but Best wrote that East Coast Māori would go to senior leaders and use the span of their bodies or limbs for standard measurements.

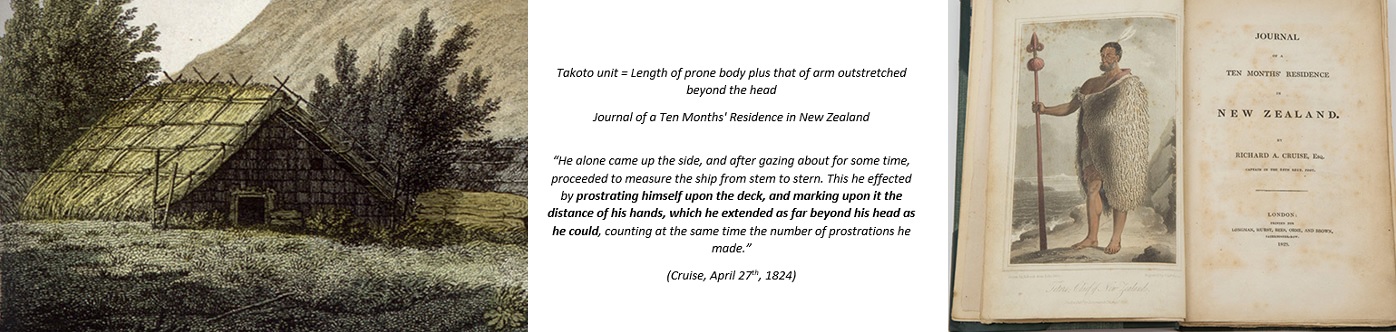

In her literature review, Te Koha found further evidence of Māori using their bodies to measure from a written account by Captain R.A. Cruise in 1823. He described a North Cape chief coming to his ship and measuring it from stem to stern by prostrating himself on the deck and marking where his hands extended to beyond his head, counting the number of prostrations he made. Best’s vocabulary list called this form of measurement the takoto, defining it as the length of a prone body plus that of an arm stretched beyond the head. In Māori today, takoto translates to “to lie down.”

Best’s work also provided evidence of Māori using a base-10 unit or a decimal number system.

There are also indications from interviews conducted in the report Nga Inenga Māori: A Preliminary Study on Māori Measurement, with Tuhoe Māori activist Tame Iti, that the measurements of a pre-European contact whare tipuna, Kuramihirangi Whare in Ruatoki, were almost similar to those of Roman and Greek temples.

Iti was told this by an architect who was brought in to help with the re-establishment of the whare. Out in the field interviewing Māori kaumātua (elders) about what they knew of old measuring techniques, Te Koha found the first anecdotal indication that Māori might have used a decimal number system in the construction of their main buildings.

Taina Ngarimu, an educator and well-known kaumātua from Whareponga Marae of the East Coast tribe Ngāti Porou, informed Te Koha that his brother, Joe Ngarimu, a builder who worked on Materoa Whare (the meeting house at Whareponga Marae), said that Māori must have had a measuring system that related to some sort of decimal system because “everything at the whare was in groups of tens”.

This would suggest that Māori may have developed the decimal measurement system further than historians have been able to document thus far.

The historian Best also published a vocabulary list of the various units of body measurements from time spent studying East Coast Māori. One body measurement was the maro, which was a unit of measurement meaning the span of the arms outstretched horizontally. The kumi, meanwhile, was a measurement of 10 maro units, which would total around 18 metres.

“The realisation that this unit is in base-10 directed the study to the ideology that Māori may have used a decimal number system and, in turn, a decimal measurement system,” says the report by Te Koha and Masouleh.

The base-10 counting system is used in most modern societies and was the most common system for ancient civilisations.

The report also says: “The importance of this should be especially emphasised because this could be considered the first step towards producing a scientific system of measurement; that is, a table of units in which one unit represents a certain number of a preceding one.”

The investigation calls for further study and conversations to add to the report’s initial findings.

Kevin Gudmundsson, manager of Length and Mass Quantities at MSL, says: “The desired goal of the research was to find out more about the measurement system used by pre-European contact Māori. This research will contribute to our documented history of measurement in New Zealand.”

Download a copy of Te Aomania's supporting presentation - A Preliminary Study on Indigenous Metrology: A Historical Approach to Pre-European Measurements [PPTX, 12 MB]